Curating as Critical Praxis : Weaving Memory against Forgetting and the Ethics of Reconstruction

Author: Dagim Abebe

Introduction

To curate Woven Memories at The Space Ethiopia - Art gallery was to enter into a silent pact with our past, the kind that linger in the frayed edges of domestic textiles, in the faded imprints of silkscreened fragments, in the deliberate imperfections of salvaged linens. Birhanu Manaye’s artwork collections enact its unsteady resurrection, demanding of me as curator complicity in a radical act of remembering.

Here, the domestic objects in Woven Memories underwent an evidentiary metamorphosis; what might appear as simple household textiles became documentations of emotional connection under Birhanu's exacting gaze. This transformation enacted a radical materialist historiography where the act of stitching becomes a quiet insurrection against erasure. Birhanu’s practice exists at the dangerous intersection of postcolonial haunting (Gordon, 2008), where the past refuses to be buried and where matter itself is agential, whispering its testimonies to those who dare to handle it. To curate this work was to confront an unsettling question: How does one exhibit what was never meant to be seen?

As both artist and curator, I moved through this project with the uneasy double vision of the insider-outsider. There was the epistemic weight of giving form to memory, balanced against the ethical vertigo of speaking for absences I could never fully know. Birhanu’s labor, his patient in obsessive layering, and his careful mutilation of domestic order, mirrored my fraught reckoning:

• Who gets to reassemble history?

• Where does preservation end and appropriation begin?

• What happens when we pull too hard on a thread that was meant to remain loose?

His practice became my archive of shadows, filled with textiles that bore the imprint of unseen hands and hands that had washed, folded, repaired, and eventually discarded these now-sacred remnants. To arrange them in a gallery was to stage an encounter between the living and the spectral, where every curatorial decision risked either repeating the violence of institutional framing or, if done with enough care, offering something like redemption.

This was an act of critical disobedience against the tyranny of "finished" histories, against the arrogance of the archive, against the notion that some memories are worth preserving while others are left to unravel. Woven Memories asked, in cloth and silence: What does it mean to hold what refuses to be held? And more dangerously: What does it do to us when we try?

To walk through Woven Memories was to move through a landscape of deliberate incompletion, where every textile, every stitch, every ghostly silkscreen whispered: Look closer, but don't presume to understand. These artworks act as a strategic refusal, dismantling the museum's obsession with grand narratives to instead honor what Carlo Ginzburg (1993) called micro-histories; those fragile, domestic traces that official archives discard as ephemera.

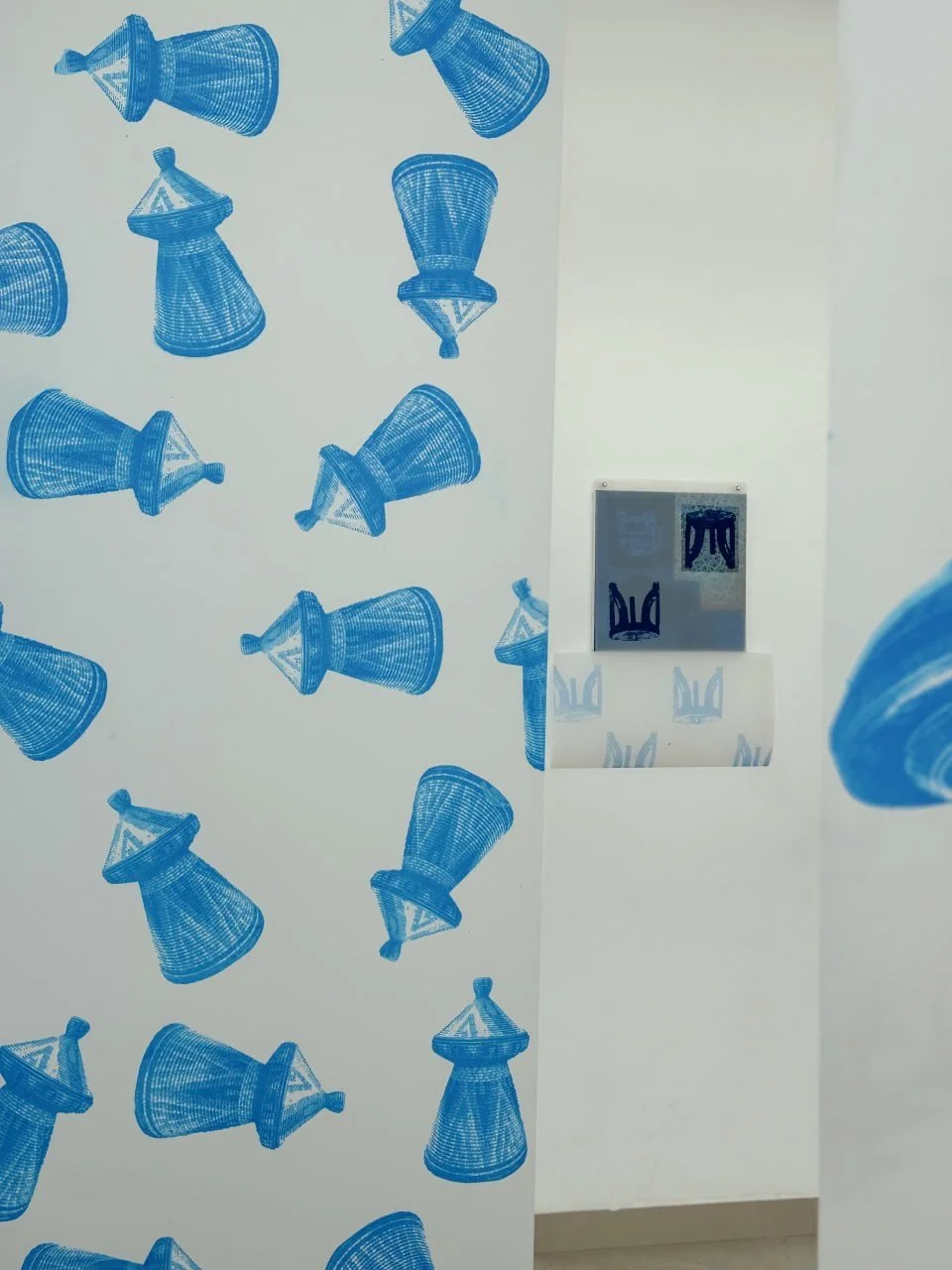

Fig. 1. Birhanu Manaye, (2025). Installation view, Woven Memories, the space Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. Image © Birhanu Manaye.

Here lies the curatorial tightrope: How does one exhibit absence without turning it into another form of consumption? The gallery, after all, has its hunger, a tendency to digest even resistance into something sleek, something sellable. My solution emerged through Mieke Bal's (2002) notion of exposition as a gesture not for the purpose of displaying, but orchestrating an encounter. I arranged the exhibition as a living circuit of historical energy, where artworks conversed across time and materiality through deliberate spatial choreography. The arrangement followed neither chronology nor medium, but the voltage of connection between fragments and the gallery space became what I call a tactical stratigraphy:

Fig. 2. Birhanu Manaye, (2025). Installation view, Woven Memories, the space Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. Image © Birhanu Manaye

Housed within the layered strata of the historic EthioPost headquarters, where modernist foundations, political reinforcements, and contemporary interventions collide, the exhibition Woven Memories transformed its architectural container into an active participant in the curation of memory, leveraging the building’s history to stage a dialectic between revelation and occlusion. The deliberate preservation of the structure’s raw, exposed conduits, and scarred masonry, mirrored the textiles’ material testimonies, while the introduction of floor-to-ceiling glass partitions bisecting the gallery created a tension between the weight of history and the illusion of transparency, refracting Addis Ababa’s urban dynamism into the static displays and forcing the city’s present to contend with the exhibition’s archival ghosts. This spatial strategy not only heightened the visibility of Birhanu’s works through shifting light and shadow but also implicate viewers in the act of remembrance, as their reflections superimposed onto fragile textiles, rendering them both witnesses and unwitting collaborators in the construction of meaning, an architectural metaphor for memory’s inherent instability, where clarity and distortion coexist, and where every attempt to illuminate the past inevitably reflects the contingencies of the present.

The deliberate placement of The River of Memory suspended in the central axis of the gallery’s architectural flow transformed the artwork into a responsive membrane between history and body. As visitors moved through the triangulated space, their footsteps generated subtle air currents that animated the work’s silkscreened plastics and frayed textiles, causing the fragments to tremble, sway, and momentarily align into legible patterns before dissolving again into abstraction. This choreography of chance movements extended Azoulay’s "civil contract of photography" into the realm of textile haptic. The result was an unscripted performance of memory itself, never static, always responsive to the present’s disruptions, yet never fully graspable. Like history’s fragile traces, the work teased legibility before dissolving again into its materiality, leaving visitors not as passive observers but as unwitting collaborators in the constant re-stitching of meaning.

Their arrangement is performed through their relationships, making visible the invisible currents that connect personal artifacts to historical ruptures. Each work became both witness and conductor in this carefully unbalanced circuit, where proximity generated meaning not through didactics, but through material empathy, the silent understanding that passes between a stain and a rust mark, between a dropped stitch and a hole.

In the end, the exhibition design performed its quiet violence, not against the artworks, but against the viewer's expectations. No clear chronology. No didactic explanations. Just the artworks that almost told their stories before retreating into ambiguity. Because some absences shouldn't be filled. Some gaps must remain wounds that won't heal into neat scars. Here, domestic textiles, patterns and objects came to die – and be reborn in his process: a ritual of calculated undoing. First, the precise violence of scissors splitting seams. Then, the slow medicine of needle and thread. Finally, the haunting of silkscreen, where ghost images of forgotten objects stain fabric. This was Walter Benjamin's (1940) "pile of debris" made manifest not as a metaphor, but as methodology.

The River of Memory emerged as the exhibition's central paradox between layers of translucent plastic and floated silkscreened fragments. These were not static images but traces in migration, bleeding at the edges where the ink resisted containment. Anna Tsing's (2015) "leakage" took physical form here – memory not as narrative current but as percolating dampness, seeping through the artificial barriers we erect against the past.

The exhibition text bled footnotes. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay's "potential history" (2019) haunted the gallery walls, turning every displayed art collection into a protest against linear time. Here, a curtain wasn't a relic, but a still-unfolding event, and its stains still spreading, its frayed edges whispering names the archive never recorded. When we cited Ousmane Sembène's "man is culture," we weren't decorating our brochure with radical chic; we were planting explosives beneath the museum's false dichotomy between "art" and "artifact." The questions that stalked us weren't abstract:

• When does the curator's hand become another form of extraction?

• How thin is the line between bearing witness and aestheticizing pain?

• Can fragility be exhibited without performing it?

Birhanu’s artistic practice elevates ordinary household objects into profound carriers of collective memory, challenging traditional hierarchies of value and preservation. By repurposing worn textiles and domestic artifacts, his work reveals how daily life quietly inscribes history onto material surfaces. A simple curtain becomes a testament to time’s passage, its fading patterns and mended tears speaking volumes about private and political realities that official archives overlook.

Fig. 3. Birhanu Manaye, (2025). Installation view, Woven Memories, The space Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. Image © Birhanu Manaye

In Woven Memories, these everyday materials were presented with deliberate reverence, their humble origins clashing against and ultimately transforming the museum’s conventional display practices. A well-mended curtain, its stitches visible like scars, was granted the same prominence. These curatorial choices forced a reckoning: What makes an object worthy of remembrance?

Fig. 4. Birhanu Manaye, Extension of self (2025). Installation view, Woven Memories, the space Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. Image © Birhanu Manaye

Birhanu’s work acts as refusing to let domestic artifacts fade into obscurity; his practice insists that history is not just written in grand events, but in the folds of a well-worn shirt, the stubborn persistence of a stain, the careful repair of a tear. These objects, once overlooked, become monuments to the endurance of everyday life. The true revolution, his work suggests, lies not in the spectacular but in the steadfast act of remembering.

The river of memory didn't hang on the gallery wall; it haunted it, and the work existed in a state of calculated disintegration, where silkscreened images of objects of daily life, objects silkscreened, bled into creating a layering of half-remembered faces. What at first appeared to be empty spaces revealed themselves, upon closer inspection, as negative imprints, ghostly absences where fabric had been meticulously unstitched thread by thread. This was curation as controlled erosion, where every display decision became an act of simultaneous revelation and concealment.

We installed the river of memory in the gallery's most vulnerable location at the central piece in between two entrance doors to the gallery with full access from both outside and inside since the wall is full glass from the slings to the floors, and the collection is full of movement, speaking back with the questions. Between the displays, there are narrow passageway spaces, where visitors had to turn sideways to pass, and their bodies briefly brushed against the work's fragile surface. This physical negotiation mirrored Glissant's (1997) "right to opacity" made manifest:

• The work refused perfect sightlines, demanding viewers move constantly to catch partial glimpses.

• Wall text was placed just beyond comfortable reading distance, forcing a choice between stepping back (losing detail) or leaning in (violating personal space)

• Lighting shifted throughout the day, as if the piece itself was fading in and out of memory.

Conclusion

Finally, as I walked through Woven Memories one last time, the exhibition whispered back to me all the questions it had etched into my practice like needle marks on fingertips:

1.The Beneficiary Paradox

Who truly gains when we frame marginal memories? The grandmother who recognizes her stitches in a displayed quilt? The academic mining for theory? The museum is boosting its radical credentials? The answer, I realized, changes with each new pair of eyes that passes through the turnstile.

2.The Spectacle Trap

We’d hung the most fragile textiles at angles that forced viewers to kneel - not in reverence, but because true witnessing requires uncomfortable positions. Yet even this careful choreography couldn't prevent some visitors from snapping Instagram shots of unraveling edges, turning our anti-spectacle into another kind of performance.

Fig. 5. Birhanu Manaye, Altered States of Being 2025). Installation view, Woven Memories, the space Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. Image © Birhanu Manaye

The gallery walls, now bare, bore ghostly outlines where textiles had hung paler rectangles that seemed to accuse us of another kind of removal. These absences became the final exhibit: proof that every act of display is simultaneously an act of displacement.

All views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

References

Gordon, Avery F. (2008). Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (2nd Ed.). University of Minnesota Press.

Ginzburg, Carlo. (1993). Microhistory: Two or Three Things That I Know about It. Critical Inquiry, 20(1), 10-35.

Bal, Mieke. (2002). Travelling Concepts in the Humanities: A Rough Guide. University of Toronto Press.

Azoulay, Ariella Aïsha. 2008. The Civil Contract of Photography. New York: Zone Books.

Benjamin, Walter. (1940). On the Concept of History (Thesis IX). In Illuminations (1968 ed.).

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. (2015). the Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton University Press.

Azoulay, Ariella Aïsha. (2019). Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism. Verso Books.

Glissant, Édouard. (1997). Poetics of Relation. University of Michigan Press.

Sembène, Ousmane. 1979. "Man is Culture." The Sixth Annual Hans Wolff Memorial Lecture, delivered March 5, 1975. African Studies Program, Indiana University, Bloomington.